In addition to my earlier article „Six essential cultural dimensions that will change how you view the world“, I would like to write about four other important dimensions that are worth considering when crossing cultures. The initial motivation was a colleague of mine who has asked me to design three more graphics as she would like to use them for her trainings. Very happy that my visualisation skills are well received, I immediately got to work and below you can see the results including a brief explanation and examples. The last dimension „Life Spheres“ is an extra I originally created for my social media channels. Here we go:

Short vs. long-term orientation

We’ve previously looked at monochronic vs. polychronic concepts of time which focus on how people get things done (one task at a time vs. a more flexible approach). This dimension, however, focuses on a different angle. Time itself is a rather abstract concept (does it even exist?) and your perception of time depends largely on your cultural imprint.

Geert Hofstede explains his research: “This dimension describes how every society has to maintain some links with its own past while dealing with the challenges of the present and future, and societies prioritise these two existential goals differently. Normative societies, which score low on this dimension, for example, prefer to maintain time-honoured traditions and norms while viewing societal change with suspicion. Those with a culture which scores high, on the other hand, take a more pragmatic approach: they encourage thrift and efforts in modern education as a way to prepare for the future.”

Examples: Translated into business, short-term oriented values include: freedom, rights, achievement, and thinking for oneself. People will focus on the profit of the current year, save and invest less, value meritocracy, vary personal loyalties with business needs, prioritize abstract rationality and analytical thinking.

Business values in a long-term orientated culture include: learning, honesty, adaptiveness, accountability, and self-discipline. People will focus on the market position, take into consideration the profits ten years from now, avoid wide social and economic differences, invest in lifelong personal networks, prioritize common sense and synthetic thinking.

Reflective question: Are you automatically picturing certain countries or people who represent one or the other end of this dimension? What is your own preference?

Let’s not be tempted by our brain wanting to correlate this information with previous experiences and store it in a specific (country) “box”. But being aware of these different perspectives, norms and values will give you a broader understanding of why people from different cultures sometimes have a hard time “being on the same page”. After awareness comes openness for creating synergies and reconciliation. For me, it is the most rewarding part of intercultural training and coaching: to help others develop new personal strategies for effective cross-cultural collaboration.

Uncertainty avoidance

Let’s start with some reflective questions:

- How do you prefer to travel? Spontaneous last minute trips or well-planned itineraries and activities?

- How do you prefer to parent? Loose or strict rules as to what is dirty, dangerous or taboo?

- How do you prefer to work? Change the employer often or not so much? Work hard only when needed or do you have an emotional need to be busy and an inner urge to work hard?

- How much uncertainty are you comfortable with?

In his book “Cultures and Organizations”, Hofstede explains: “The dimension Uncertainty Avoidance has to do with the way that a society deals with the fact that the future can never be known: should we try to control the future or just let it happen? This ambiguity brings with it anxiety and different cultures have learnt to deal with this anxiety in different ways. The extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations and have created beliefs and institutions that try to avoid these is reflected in the score on Uncertainty Avoidance.”

Hofstede points out that uncertainty is a subjective experience, acquired and learned. The coping strategies (e.g. technology, laws, religion) are reflected in our culture, based on nonrational roots, leading to sometimes incomprehensible patterns of behaviour from an outsider’s perspective.

On a side note, do not confuse uncertainty avoidance with risk avoidance. Risk evaluation is very specific (measurable in probabilities and percentages), uncertainty is rather diffuse.

Example: Team A ranks low on the uncertainty avoidance dimension. People on the team are creative and flexible. They thrive on developing new ideas and innovative products. Team B is more uncertainty avoidant and team members value sense of detail and project planning. These teams, rather than working against each other, have a great potential for creating synergies. The innovative team supplying ideas and the project team developing and implementing them. That’s the theory… Putting it into everyday practice is a whole other story! Intercultural trainers can make a valuable contribution here.

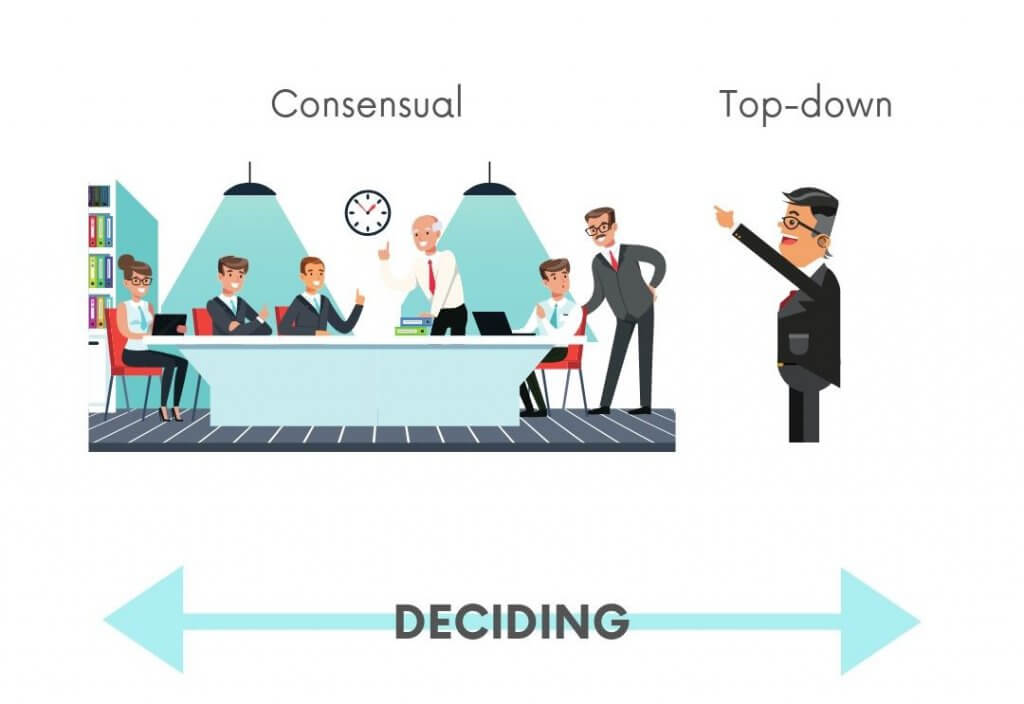

Deciding

In her book “The Culture Map”, Erin Meyer points out two different aspects of leadership. Egalitarian vs. hierarchical leadership is one dimension (see earlier post). Consensual vs. top-down decision-making is the other. Why differentiate?

In most cultures, being egalitarian goes along with consensual decision-making and hierarchical correlates with top-down decision-making. But there are exceptions as you can see on the following picture and these can be consternating:

Meyer explains: “While Americans perceive German organizations as hierarchical because of the fixed nature of the hierarchical structure, the formal distance between the boss and subordinate, and the very formal titles used, Germans consider American companies hierarchical because of their approach to decision making. German culture places a higher value on building consensus as part of the decision-making process, while in the United States, decision making is largely invested in the individual.”

In Germany, more time is spent on coming to a group agreement. But remember, these are rough generalizations and, when talking about dimensions, everything is relative. If you ask around in the Netherlands, they will not perceive Germans as consensual at all.

When working or leading cross-culturally, this dimension bears great potential for conflict. Being aware of the cultural imprint and individual preferences in your team is crucial for success.

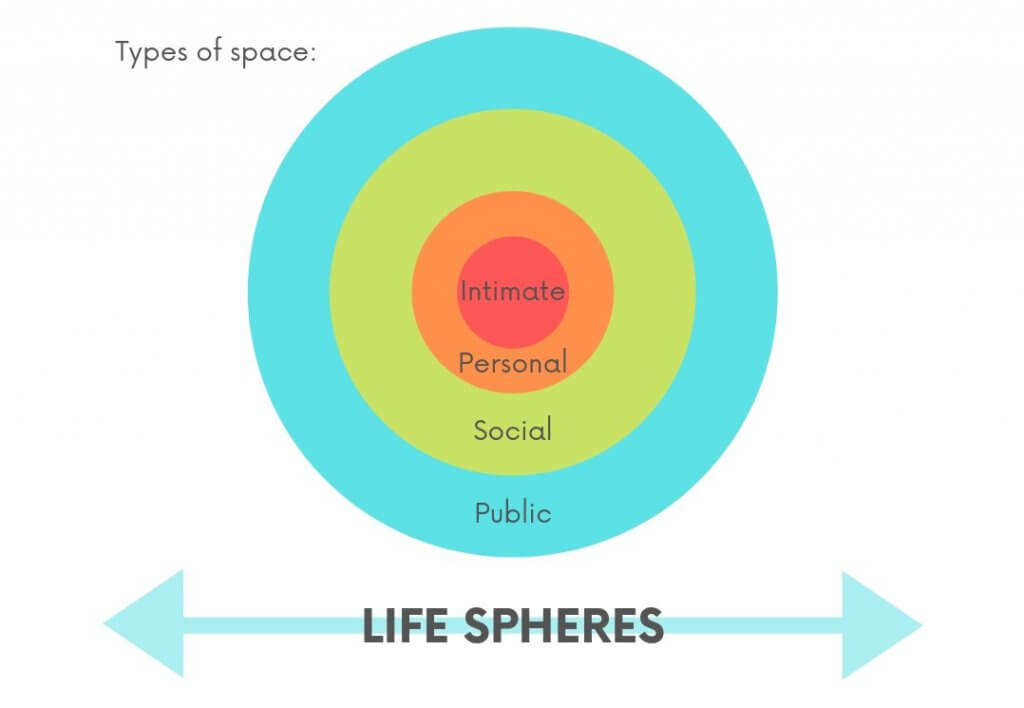

Life spheres

This may not be a classical dimension, but a very useful model to improve cultural awareness. It originates from Edward T. Hall’s research on proxemics, the study of human use of space and the effects that population density has on behaviour, communication, and social interaction. As it happens with many of the cultural dimensions, we are often unaware of this hidden component of interpersonal communication. And what makes it so interesting for intercultural encounters: It is strongly influenced by culture.

Hall identified four types of space or interpersonal distances:

Intimate – up to 18 inches (46cm)

Reserved for closer relationship and greater comfort between individuals, for hugging, whispering, or touching.

Personal – 1.5 to 4 feet (46-122cm)

For people who are family members or close friends. The closer people can comfortably stand, the higher the level of the intimacy.

Social – 4 to 12 feet (1.20m-3.70m)

For individuals who are acquaintances. With someone you know fairly well, such as a co-worker you see several times a week, you might feel more comfortable interacting at a closer distance. In cases where you do not know the other person well, such as a postal delivery driver you only see once a month, a distance of 10 to 12 feet may feel more comfortable.

Public – 12 to 25 feet+ (3.70-7.60m+)

For public speaking situations. Talking in front of a class full of students or giving a presentation at work are good examples of such situations.

Interesting that he defined exact distances in inches and feet. Is it really that universal? I assume that within that range, cultures and personal preferences differ significantly. Here in Germany, people value their personal space a lot and it influences many areas of social and public life. Silence waggons on trains, distant handshakes, approach to service in shops, … just to name a few. If you come from the other end of the range and are not consciously aware of the differences, this can result in rather painful experiences of exclusion, rejection, unfriendliness. Again, my advice for both sides is to not take things too personal. Usually it’s not about you, its about the other person’s own preference of interpersonal distance.