Introduction

In July 2019, I shared a selection of what I consider the most insightful cultural dimensions on my Instagram account. I felt that before looking deeper into a specific cross-cultural situation, it is important to learn about the main cultural differences that can be found across the globe. The so-called dimensions are exactly that, dimensions, a range, no absolute figures, no fixed point on a scale. They help us give a general orientation on what we could expect in a cross-cultural encounter and offer us a framework to become more aware of our own cultural imprint and personal preferences.

Dimensions say absolutely nothing about any individual or a specific situation, so be careful when applying them, they are only part of the story. Always make sure to also consider the context and the individual personality of the person involved. Be open, listen, ask questions, learn and then draw your conclusions.

I decided to put all six Instagram posts together in one document and share this with you in the resource section of my website (free download here). It is to give you a first overview on some of the concepts that we work with in intercultural training. If you want to find out more, I recommend you check the literature that I am referring to. Each dimension includes an explanation, an example and a reflective question. You are welcome to use this material wherever it may be helpful, just mention the source. Enjoy the read!

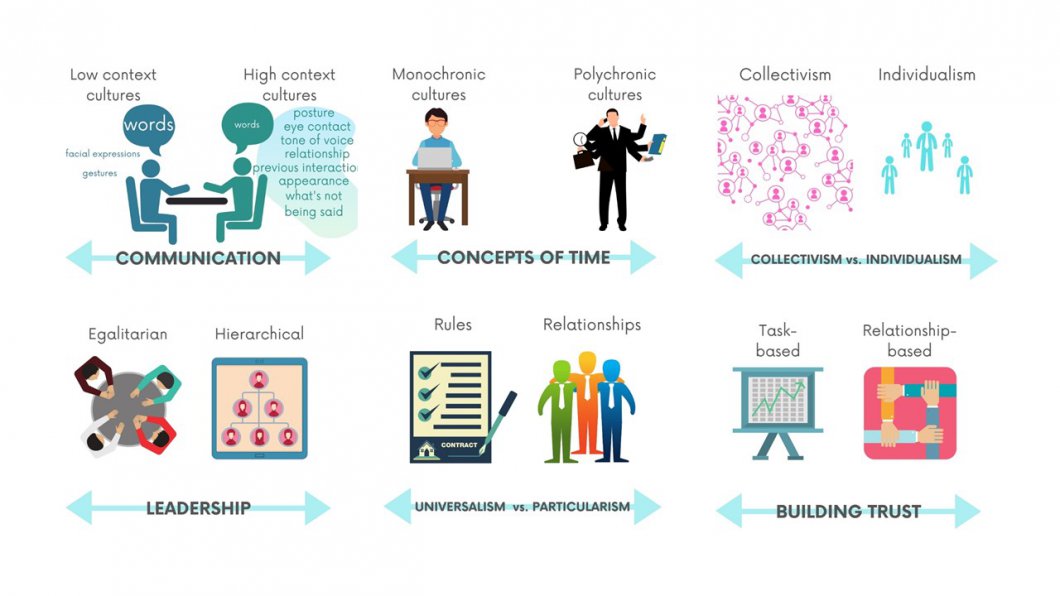

Communication

It’s all about communication, isn‘t it? And it’s the hardest. Look at how we sometimes struggle to communicate in our own culture (thinking of how hard this can be in a partnership!). No need to say that cultural factors make it a lot more complex.

An example: When I offer my Persian friend a cup of tea, in the first attempt she will decline, because that is a sign of good manners in her culture. As someone from a low context culture, I would take her words literally, not pour her any tea and not ask again. She might be shocked, because in her culture, people ask several times and then you say yes. If you are unaware of all this context, you will not get the cues. And that Persian friend will go home thirsty and think what a strange, unfriendly culture this is.

The dimensions “low context” and “high context” were described by the American anthropologist and cross-cultural researcher Edward T. Hall in the 1950s. Low context cultures need very little context to communicate. They say explicitly what the mean and they mean what they say. High context cultures give a lot more importance to the context and the actual words can only be interpreted correctly with that context.

Both types have their pro’s and con’s. There is no right or wrong, better or worse. The tricky part is that we are often not aware of these differences and then make the mistake of reading the other person’s communication in the same way that we are used to. We see things from our own cultural perspective, and we tend to think it is the “best” way to do it. This is called ethnocentrism and leads to a lot of – often very painful – cross-cultural misunderstandings.

Reflective question: Which type are you and have you experienced a painful misunderstanding due to these different communication styles?

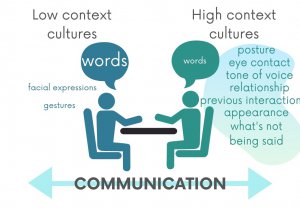

Concepts of time

As we all learned in school, time is relative! here are many different concepts of time. Edward T. Hall, the American anthropologist I already mentioned yesterday, laid the foundation of how we look at time from an intercultural perspective today. He has observed two different main societal approaches to time: monochronic time cultures and polychronic time cultures. E. T. Hall makes it clear that these two types do not mix, it’s either one or the other. A tough pill to swallow, especially when you are working across cultures and want to build bridges to foster a good collaboration. But I have a nice example how good collaboration can work.

Monochronic cultures, such as Northern Europeans, Americans or Japanese, view time as tangible and concrete. Time is precious and a system that orders life. “We speak of time as being saved, spent, wasted, lost, made up, crawling, killing and running out.” (E. T. Hall). Monochronic time perception is not natural to the human, it is learned, and the industrial revolution is considered to be one of the main drivers. Food for thought!

Polychronic cultures, mainly to be found in Southern Europe, Latin America, Africa and Middle East, but also China, take a flexible approach to time, involvement of people, and completion of transactions. They are involved in several different things at the same time (not to be confused with multi-tasking) while the focus lies much more on relationships and reacting to changing circumstances.

Example: A German friend of mine (monochronic type) wants to visit his customer in Venezuela (polychronic type). Instead of sending an email with a formal request, which in the past has led nowhere, he uses his informal network. His local agent will talk to a few people to find out if it is a good time to visit the customer. The German then flies over without having an appointment (this is unthinkable in monochronic terms!) and pays the customer a visit. He is told by the secretary that his customer is not available all day. Instead of giving up, the German comments that that’s no problem and asks if he can stay around for a while and uses the time to work on his laptop. After 2 hours the customer eventually comes out of his office and sees the German supplier. He greets him warmly, invites him to join him for lunch and spends the rest of the afternoon with him discussing business.

The way we see time goes very deep and is the source of a lot of intercultural misunderstandings. People from one type find it very hard to fully understand and embrace that there is a valid other type. Each side is very convinced that their way of dealing with time is the best way. That’s where the intercultural trainer comes in handy!

Reflective questions: Which type are you? If you have worked cross-culturally, what is your strategy for a good collaboration?

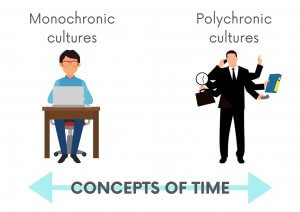

Collectivism vs. Individualism

Have you heard this joke? “If everyone thinks about themselves, then everybody is taken care of”.

Collectivism means that the wellbeing of the group comes before individual preferences. The “ingroup” is expected to look after an individual in exchange for loyalty.

Individualism focuses on personal goals and values independence and self-reliance. Belonging to a group comes second.

It is hard to describe this complex dimension with only a few words, so let me just say how important it is to explore it further. It has great influence on how we do business across cultures, it affects negotiations, decision making, motivation and many other areas. Also, on a personal level we can learn a lot about our own preferences and potential inner conflicts that we carry around.

Example: An engineer from a more individualistic society was sent to his company’s production site in a collectivistic society to find out why a certain machine has not been performing well. After analysing everything, he found it to be a human error and could narrow it down to one person who seemed to repeatedly handle the machine in a wrong way. He spoke to that person in front of everyone and explained in calm manner how it should be done right. That person’s team was shocked and she was highly ashamed and unable to improve her work. She tried to continue her work but repeated the same error again. The engineer was gradually losing his patience and became louder as he repeated his instructions. She left work early and it was unclear if she would come back at all. The engineer was puzzled and shocked about what had happened. Fortunately, the next day, the engineer apologized deeply and the matter was handled with more tactfulness. But face and trust were lost.

Reflective question: In which situations do you put the wellbeing of the group before your individual preferences? And when do you put your own interests first?

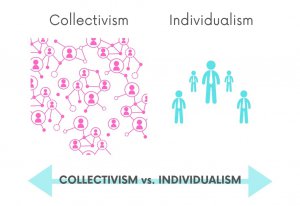

Leadership

In literature, you will find different ways of describing this dimension, I chose to follow the one used by Erin Meyer in “The Culture Map”, one of my favourite books to refer to when carrying out corporate trainings. It is closely linked to the dimension “Power Distance” coined by Hofstede and the Globe study.

Let’s start by the reflective question today: “What does a good boss look like?” Erin Meyer asks the readers in her book. Close your eyes for a moment and picture that person. Clothes, posture, facial expression, how you address that person, how he/she travels to work, etc. And now check if that person has more traits of an egalitarian or hierarchical culture:

Egalitarian cultures:

– It’s okay to disagree with the boss openly and in public.

– People are more likely to move to action without getting the boss’s okay.

– If meeting with a client or supplier, there is less focus on matching hierarchical levels.

– It’s okay to e-mail or call people several levels below or above you.

– With clients or partners you will be seated and spoken to in no specific order.

Hierarchical cultures:

– An effort is made to defer to the boss’s opinion especially in public

– People are more likely to get the boss’s approval before moving to action.

– If you send your boss, they will send their boss.

– Communication follows the hierarchical chain.

– With clients or partners you may be seated and spoken to in order of position.

Intercultural misunderstandings arise, when we are not aware of the different expectations that come with different concepts of leadership. An egalitarian manager might be very unsuccessful in a hierarchical culture as he might be perceived as a weak, ineffective and incompetent leader as it seems that he gives all the power to his staff. Vice versa, a hierarchical leader might be shocked by the lack of respect that egalitarian staff is showing him/her and might feel completely ignored. Also, it is crucial to understand that if you are managing people who are used to hierarchical leadership, they expect a lot more detailed instructions on the work that is expected. When you lead in egalitarian cultures, it is important to give people space to develop their own ideas.

Universalism vs. Particularism

This dimension was introduced by Fons Trompenaars, a Dutch organizational theorist and management consultant to describe the challenge of balancing rules and relationships. Or, as he calls it, “reconciling” the two. You will find many examples and strategic tips in his book “Riding the waves of culture”.

Universalism

People place a high importance on laws, rules, values, and obligations. They try to deal fairly with people based on these rules, but rules come before relationships. Typical traits: Consistency, uniform procedures, demanding of clarity, letter of the law

Particularism

People believe that each circumstance and each relationship dictates the rules that they live by. Their response to a situation may change, based on what’s happening in the moment, and who’s involved. Typical traits: flexibility, “It depends”, at ease with ambiguity, spirit of the law

Example (given by Trompenaars): “You are riding in your car driven by a close friend. He hits a pedestrian. You know he was going at least 35 miles per hour in an area of the city where the maximum allowed speed is 20 miles per hour. There are no witnesses. His lawyer says that if you testify under oath that he was driving only 20 miles per hour, it may save him from serious consequences.”

Reflective question: “What would you do in view of the obligation of a sworn witness and the obligation to your friend?”

The fascinating part of his story is what happened when he confronted different cultures with the results of the others. Both sides of the dimension concluded that the others were corrupt and that they cannot be trusted! “They always help their friends!” versus “They don’t even help their friends!”. If you are curious, watch the full Tedx Talk by Trompenaars on YouTube, it’s very funny and insightful.

Building Trust

The head or the heart? Cognitive or affective trust? This dimension is also taken from Erin Meyers “The culture map” and refers to business contexts. It is always a big topic in my Mexico trainings for Germans and vice versa!

Task-based cultures: Trust is built through business-related activities, accomplishments, skills and reliability.

Relationship-based cultures: Trust is built through sharing meals, evening drinks or visits at the coffee machine. It arises from feelings of emotional closeness, empathy, or friendship.

For a person that is used to working in a task-based culture, it can be very hard to adapt to a relationship-based business partner. A little small talk should be more than enough to get started on the actual business matters, then finish up with a quick working lunch (some sandwiches will do) and then head back to the airport for the next customer. That’s efficient, straight to the point and professional. But extensive conversations about seemingly personal topics, long lunches or dinners, several days of discussions, meetings, dinners, excursions…? That’s way too much!

On the other hand, in a relationship-based culture, the hurried behaviour of a task-based person might come across as impolite, cold and self-serving. Why the rush? First, they need to find out a bit more about this person, their way of thinking, check their ethics and if this is a person they can trust with a long-term business relationship.

To build a bridge between the two, it is recommendable to invest some extra time in a relationship-based approach. Once a good base is established, collaboration will run a lot smoother and task-based work style will be more easily accepted.

Reflective question: Make a quick list of 5 people from different areas of your life that you trust. Then think about what led you to trust them.